I had to laugh when I read this in The Oxford Book of American Poetry: "I write in the American idiom," William Carlos Williams noted, "and for many years I've been using what I call the variable foot." One of the secrets of American poetry is that no one knows what the variable foot is.

It's that dark time of year when I settle into writing and don't think about the outside world, and when I revisit books I love. Over Thanksgiving I found myself once again flipping through my favorite anthology, which I blogged about here

And also discovered new books, like Dante di Stefano's Love is a Stone Endlessly in Flight, which I loved so much, I had to interview him. And Claire Bateman's Scape, which totally blew me away.

I don’t even know how to describe Claire except to say that I remember a review (which I can't find right now) in which she was called a modern day Hopkins. Like Hopkins, she really does seem to come from another world. She loves to play with your mind, or simply illuminate it for you, as in her poem, “A Few Things to Know about Reading,” which begins:

I. If a book hasn’t shaken you up even a little after three chapters, you must lay it aside since the very purpose of reading is to set all your pervious clarities resonating at incompatible frequencies.

II. Do not mistake reading for actual life, which suffers from lack of both compression and dynamic focus; not the prolonged mundane stretches no editor would stand for, the proliferation of character and incidents that apparently do nothing to advance the plot. Also, as you may have notices, the protagonist comes across as muddles, inept, though neither in the comedic for in the ironically reflexive post=tragic sense. The main problem with reality is that you aren’t allowed to skim it.

III. Do not mistake actual life for reading. Inside your brain, there is no homunculus waxing lyric on the events of your day, so you must quit feeding him truffles, and shoo away his attendants with their ostrich-feather fans.

Forgive the political nature of this comic. All week I have been thinking of this Edward Lear poem. And how as a girl, whenever my mother read it, I would complain that you can't possibly go to sea in a sieve--

to which she answered:

Why, there's nothing to worry about! Because you can always sleep in a crockery-jar with your feet wrapped in pinky paper, all folded neat, and fastened with a pin.

I think that's my favorite stanza of the poem:

The water it soon came in, it did,

The water it soon came in;

So to keep them dry, they wrapped their feet

In a pinky paper all folded neat,

And they fastened it down with a pin.

And they passed the night in a crockery-jar,

And each of them said, ‘How wise we are!

Though the sky be dark, and the voyage be long,

Yet we never can think we were rash or wrong,

While round in our Sieve we spin!’

Far and few, far and few,

Are the lands where the Jumblies live;

Their heads are green, and their hands are blue,

And they went to sea in a Sieve.

("What If You Slept" by Coleridge has always been one of my favorite poems.)

The other day I was listening to two of my poet-friends complain bitterly about their parents. Among other things, they talked of how they wished their folks had an interest in literature. No one in their families read books. I couldn’t join in. After all, I grew up in a house of wall-to-wall books. I will never be as literate as my parents, and I owe much of what I know about poetry to my mother who read aloud from my earliest memories. I used to frustrate her to no end, asking her to stop when I liked a line or poem, and read it again. And then again.

Not again? she’d say.

Just one more time, I’d say. And we’d go around and around.

And in my mind, later, I would play with the lines. So as a girl this poem might be:

What if you slept

And what if

In your sleep

You dreamed

And what if

In your dream

You went to heaven

And there—there was a rain shower

And when you awoke,

You were soaked to the bone . . .

Or:

And there—you discovered secret powers

And when you awoke

You could see through walls . . .

Or:

And there—your soul was made of sugar and flour

And when you awoke

You knew you were destined to be a baker . . .

Or:

And there—you climbed to the tip of God’s tower . . .

And when you awoke

You were still holding an angel by the finger . . .

I would keep going and going. This was one of the ways I passed my time. I called this game making-and-filling-in-the-blanks. I always liked games of fill-in-the-blank. My mother said if I continued in this way, I would never remember the correct versions of poems. She was right.

This is my latest post for the Best American Poetry Blog

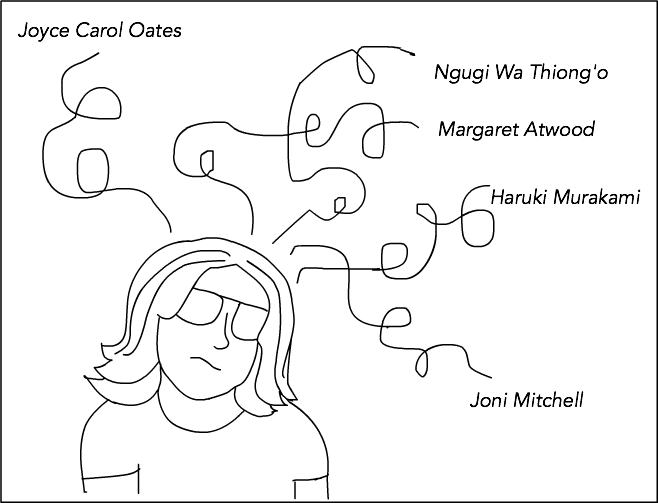

After hearing about the Nobel Prize for Literature, I was reminded of my first grade class, particularly of a workbook for what was then called New Math. The workbook included pictures of sets of objects. Students were supposed to circle the object that did not belong. So one picture might include a bird, a dog, a pig, and a sandwich. The next, a fork, a spoon, a knife, and a tennis shoe. The next, a ring, a watch, a necklace, and a frog. What this had to do with math, I am still not certain.

But I liked the pictures, and I loved to think up stories in which one might want to include the circled items. I would explain to Mrs. Wallace, my teacher, that a sandwich could be used to feed the bird, the dog, and the pig. A fork comes in handy if you have a knot in your shoelace. The frog, of course, might have been a prince or princess once upon a time.

I was also reminded of discussions I had with the poet, Eleanor Ross Taylor, back when I was just out of college and first trying to understand the literary world. Eleanor had an acerbic wit and was unsparingly honest. Literary prizes, she suggested, are not all that you think they are. She talked at length about the different presses and literary connections and publishers one might wish to have, and I remember feeling so discouraged. I concluded that literary success is a bit like economic success in our country. There is the top tiny %, now referred to as the 1%, and that one dreams of becoming a part of, and then there is the 99%.

Eleanor also suspected that certain winners are actually compromise candidates. It’s hard to come to a consensus, she said, adding, we writers don’t agree on many things. That was especially true for Eleanor and me. She loved to ask me who my favorite writers were, but inevitably she would tell me how much she disliked them. About my beloved Garcia Marquez, she said, I simply cannot abide him. Of the French surrealist poets I adored in those days, she said, Really, I’d rather not get a headache. But you just tell me why I should. Once, when I showed her a poem by Russell Edson, she said, I don’t know what that is. Do you? And we both burst out laughing.

https://cavankerrypress.wordpress.com/2016/09/26/nin-andrews-interviews-donald-platt/

http://www.poetsandartists.com/magazine/2016/9/27/grace-notes-grace-cavalieri-interviews-nin-andrews

An excerpt:

GC: Seeing the outer edges as you do, with so much humor, were you always that way as a child?

NA: To a certain extent, yes. I have always lived on the outer edge. I have always been a little bit of rule-bender, or someone who resists the flow. As a girl, I developed this rule or habit—that if someone told me not to do or say something, I did it. Or rather, I often did it. (I did use some judgment.) Good things resulted. So I continued with this habit.

That’s how The Book of Orgasms began. A professor told me not to use the word, orgasm, in a poem, and not to write about orgasms. Never mind that my orgasms were messengers from the divine . . .

This habit is also how, or maybe why, I met David Lehman. My college advisor despised David and told me never to take a class with him. (You know how English departments can be.) Before my advisor told me that, I had no intention of taking another poetry class, but, in an instant, I changed my mind. I left my advisor’s office and walked straight up these creaky wooden stairs and turned to the right, right into David’s office. I had never met him before. Are you Dr. Lehman? I asked in my polite voice, looking down at his desk at a copy of The Selected Poems of Frank O’Hara. He blinked a few times and said, Yes, may I help you? I blurted out that my advisor had just suggested I take an independent study with him. (I think he knew I was lying.) That was the beginning of a long mentorship and friendship. I will add that if it had not been for David Lehman, I would not be a poet today. It was David who said, in his tactful way, that I was odd. Or different. And that being odd is a gift, not a curse.

What a thrill to be amongst such great writers. I have to admit, I was starstruck. Yep, that's me next to Wil Haygood, grinning like a fool.

Connecting Readers and Ohio Writers

MEDIA RELEASE – July 18, 2016

2016 Ohioana Award winners Announced

Literary prizes to be presented September 23 at Ohio Statehouse

Columbus, OH (July 18, 2016) —The Ohioana Library has announced the winners of the 2016 Ohioana Book Awards.

The awards, established in 1942, honor Ohio authors in Fiction, Nonfiction, Poetry, Juvenile Literature, and Middle Grade/Young Adult Literature. The final category, About Ohio or an Ohioan, may also include books by non-Ohio authors. The Ohioana Awards are among the oldest and longest-established state literary prizes in the nation.

“From the nearly 300 books that were eligible for this year’s awards, thirty finalists in six categories were selected by jurors,” said David Weaver, Executive Director of the Ohioana Library. “To make this short list is itself recognition of excellence and selecting a winner is a challenge. The books and authors chosen as 2016’s honorees are truly stellar.”

This year marks the 75th anniversary of the awards, which will be presented at the Ohio Statehouse in Columbus on Friday, September 23.

The winners are:

Fiction

Mary Doria Russell. Epitaph: A Novel of the O.K. Corral. Ecco, 2015.

Nonfiction

Wil Haygood. Showdown: Thurgood Marshall and the Supreme Court Nomination That

Changed America. Knopf, 2015.

About Ohio or an Ohioan

David McCullough. The Wright Brothers. Simon & Schuster, 2015.

Poetry

Nin Andrews. Why God Is a Woman. BOA Editions Ltd., 2015.

1. Different Ways to Say Fuck

I had five eye operations as a girl. After each one, I imagined myself emerging with perfect and uncrossed eyes. I would wait anxiously for the day I could peel back the bandage. But the surgeries were never entirely successful. The doctor always suggested that I have just one more operation.

These operations were complicated by my reaction to the anesthesia. The eye doctor had difficulty waking me after surgery. He once called me his Sleeping Beauty, but it was a sleep that worried him. I was sick, too, and usually confined to bed for a week or two afterwards.

During that time of recovery, my mother would visit my room with a pile of old books to read aloud. She always chose volumes of myths, fairy tales, poetry, parables, or folk tales, usually antiquated books with beautiful pictures and ornate language. She read one story after another, hour after hour, as I lay, dozing, hypnotized by her beautiful reading voice. A former school teacher, she liked to ask questions about the stories. My answers, she complained, didn’t stay close to the text. I usually told her what a story reminded me of.

When I was eight and recovering from my third operation, for example, my mother read me the myth of Persephone. I said the myth made me think of a fight I had had with Trig, the farmhand’s son, a fight that began when he asked, You see what those cats are doing? pointing at the mating tabbies, Tigger and Rain. People do that, too. Only they call it fucking. And one day I’m gonna’ fuck your sister, Sal. I couldn’t help it. I slugged him as hard as I could. That was the day I got my first black eye.

My sister, I told my mother, was like Persephone. Only she wasn’t stolen yet.

My mother blinked a few times before saying, You shouldn’t get in fights. It’s not ladylike. And then she added, Don’t ever use that word again. And you know which word I mean. If you ever tell a story like that, find another way to say that word.

What other way? I asked.

Think about it, she said. You’re a smart child. For every word you use, for every sentence you speak, there are many other and better words or sentences to say the same thing.

For years after I thought of different ways to say fuck.

***

- Fucked Up

In my freshman year in college, I had a nervous breakdown. I rarely talk about this. Instead I prefer to edit that year out of my life. But the fact remains; I developed what I called a stutter in my mind. I felt as if I were becoming a stuck-record, going over and over the same sentences, thoughts, and ideas.

I don’t know if this experience is particularly unusual—after all, many people obsess. But it became a problem when I was writing. I would try to write a paragraph, but struggle to get past the first line. I would write and rewrite it as many as ten times. Then I would do the same with the second sentence and the third. When I completed a paragraph, I would revise it.

I would also change my topic, or my approach to a topic.

This problem began when I had a certain professor, Dr. B., who assigned an essay a week and then insisted on examining every sentence his students wrote, suggesting alternate ways of saying the same thing. He wanted to open us up to the possibilities of the imagination, grammar, and the English Language.

I can still hear his voice in my head as he read aloud one of my essays, pausing again and again to say, This sentence works okay, but how could you say it differently? Or, Are you certain that’s how you want to say this? If I didn’t answer, he would suggest alternatives.

After a while I saw every sentence as many sentences, or as a potential multiple choice test.

Worse were the grammatical options the professor offered. In this paragraph, he said once, I see three compound sentences in a row. Why not rearrange the third sentence so that you have an introductory subordinate clause? And break up the second sentence into two simple, declarative sentences.

A grammarian I will never be.

Soon my choice of sentence structure became another kind of multiple choice test. Or a game show. Will it be sentence structure number 1, 2, or 3?

I also found myself pondering the use of commas, particularly the Oxford comma which he preferred to leave out but said, at least in some cases, is necessary. And the comma before which, which is used when which is nonrestrictive but not when which is restrictive, and which I still find confusing. A case in point: the which in the first sentence of this paragraph.

It’s just comma sense, the professor would joke, but I wasn’t sure I had it.

In addition, there were the professor’s obsessions, particularly with the conditional and subjunctive cases. He said on one of my papers, Your use of the subjunctive is correct here, I think, but not necessary because the conditional would serve just as well unless you really think uncertainty is paramount. You should know that use of the subjunctive is currently in decline in the English language. But the conditional is also not ideal. Why not write in a more assertive tone?

He especially disliked semicolons. He hated how we students used them willy nilly, saying, The link between two independent clauses must be logical if one is to use a semicolon, just as the link between human beings should be logical if they are to get married, but of course, it rarely is.

And there were also the problems with the elliptical clause, as in better than me vs. better than I, and the split infinitives, and sentences ending with a preposition.

Finally there was his suspicion of the zeugma. Your compound direct object, he said once, could be considered a zeugma, but I would want to know that you know what a zeugma is. And that you decided consciously to use one here. Otherwise consider changing or dropping this sentence.

Instead I said I needed to drop out for a while.

Why? he asked me, looking startled. I said that I had just changed too many sentences, paragraphs, and my mind. Sometimes there is no more time for decisions and indecisions and visions and revisions. I was trying to be funny.

I am sorry to hear that, he said, adding under his breath, That’s fucked up.

***

- In Defense of Madness

That fucked up experience, or mind-stutter as I call it, has haunted me ever since. I still rewrite excessively, trying and failing to correct my grammatical errors. I still think I should edit any piece of writing, at least one more time. I still dream I am in Dr. B.s class, writing and rewriting those weekly essays. And I remember many of essays from his class. After all, I tried to write them as many as twenty or thirty times.

Just last week I was reminded of the essay I wrote on Jane Eyre when I watched a video by the amazing Jen Campbell, who, in her witty and entertaining style, illuminated aspects of the text and offered her insights, including the idea that Bertha is an aspect of Jane. (Who else could get 4,000 people to watch a talk on Jane Eyre?)

I was reminded of my title from freshman year, In Defense of Bertha, and how I wrote that many women should have a mad woman in their attic. After all, I was meeting aspects of my own just then.

I remember how I wasn’t certain that I could or should write about madness, Bertha’s or my own. My professor pointed out, I spent entirely too much time in the conditional case, pondering and overusing the words like perhaps, probably, maybe, might, would, should, and could.

He added that women are more prone to this problem, which he called conditional-overuse, adding that men speak more naturally and emphatically, a comment which has stuck with me and might or might not be true. Perhaps and maybe. Either way, it’s maddening.

***

- THE SEVEN SWANS

The more I worked on my Jane Eyre essay, the less I said about the book or Charlotte Bronte.

Instead I wrote about the fairytales my mother read aloud to me, specifically about the princesses in fairytale towers (Rapunzel, Maid Maleen, Sleeping Beauty) who were and weren’t like Bertha in her attic. The princesses were, instead, pre-Berthas. Prepubescent. Still waiting for their moment to be kissed and liberated. Or to be de-towered and deflowered.

Like Persephone, they were unwittingly waiting for a king to sweep them away. But would he be a king of the underworld or this world? And how could they not want to scream?

And then I began to digress even further . . .

I wondered whether fairytales ever put men in towers—or in some purgatorial space between heaven and earth. I concluded that there was one fairytale, The Seven Swans, where this is the case.

In The Seven Swans, seven brothers are trapped in the bodies of birds. And it is a girl, or their sister, who breaks the evil bird-spell and turns the swans back into men. But she doesn’t completely succeed. One brother is left with a wing in the place of an arm.

(Forgive me--I am short-changing the story here, skipping important details including the fact that the sister-savior of the story also spends time in a tower. And she is, of course, rescued and married to a king.)

I wondered if the sister worried forever after about the wing she didn’t fix? Did she stay awake at night, thinking of that single wing, dreaming of it rising out of her youngest brother’s back.

The wing, I think, is emblematic of how people live happily and unhappily ever after with their odd limbs, their crossed eyes, and troubled minds. Of how, after being poisoned or possessed, after becoming a bird or a sleeping princess or a prisoner of the underworld, one is marked for life. No matter how many hours of therapy one endures, a trace of the sleepiness or poison or the wing is still there. It can be tucked beneath a jacket or otherwise disguised. But the mind remembers, even if it wants to rewrite the past and make it perfect. And then rewrite it again.

I have always loved the image of a man with a single white wing.

This was previously published on Best American Poetry's blog

This was first posted on Best American Poetry's blog.

When I was girl, I remember driving past the jail in downtown Charlottesville. I don’t know if my memory is accurate or if I only imagined I could see men moving behind the bars—just the tops of their heads.

Who’s in there? I asked my father, imagining men on the FBI’s Most Wanted list.

Just some fools down on their luck, he said.

Do you know any of them? I asked. He just laughed.

It was a reasonable question. Over the years, a few criminals worked on our farm. (My husband suggests I not elaborate for fear of former farmhands who might read my poetry.) By criminals I don’t mean the petty thieves like Charles who stole farm tools, or compulsive liars like Toby who spent most of his working hours drinking and catching snapping turtles from our mud pond, or unpredictable men like Fred who let the heifers loose on the freeway one night. No, I mean the pedophile, the drug dealer, (okay he was just a marijuana-dealer), and the man who stole a neighboring farmer’s tractor and killed his wife. (But it was a crime of passion, my parents explained, as the murderer continued to work for them for another forty years.)

As far as I know, none of these men went to prison. Or if they did, it wasn’t for long.

***

My parents’ friend, Betty Smith, told me once that people who lived through the depression, as she and my folks did, had grown accustomed to hiring some of the strange men who wandered up the dirt roads, seeking employment.

She was visiting on the day Ernest Holmes arrived at our farm in a Yellow Cab, looking for work. Earnest claimed to be, among other things, a traveling barber. Anyone need a haircut? he asked, lifting his black bag from the cab. Intrigued, my mother said, Why yes. She selected me to be his guinea pig.

Together we watched as Ernest set up shop, seating me in a folding chair, wrapping a dish towel around my neck, and placing a blue plastic a bowl on my head before cutting circles around and around the bowl, my hair getting shorter and shorter until it was shaped like a shaggy Yarmulke. My mother immediately hired him to be a cook.

Cutting hair and cooking weren’t Ernest’s only skills. He also taught me to drive. And drove me and my sister all over town—to various lessons and school events. With six children in a family, someone always needed to go somewhere.

After several years of working for us, Ernest was pulled over by the cops. It turned out he didn’t have a license.

This experience might have upset other parents. Mine just laughed.

***

The two things my mother and father shared were a subversive view of the world and a dark wit.

While they wanted their children to be high achievers and were proud of their valedictorian and their goody-two shoes daughters, they were most impressed by their rebellious daughter. They never stopped bragging about my sister who, given a set of true-false questions, got them 100% wrong.

Once or twice, when I was sent home with a note from the teacher for bad behavior, I watched as they first tried to suppress a grin and then broke out in giggles.

They both loved stories of tricksters, escape artists, and clowns: the Pucks, the Brer Rabbits, the Houdinis.

Whether it was Aesop’s fable about the fox that tricked the crow, or the Bible story of King Solomon and the two women, or Odysseus with the Trojan horse, I can still hear my mother practically crowing, You see? He outwitted them.

When she was an old woman, I read my mother some of the Nasreddin stories. She laughed and laughed. How silly, she would say. Read me another one.

She particularly liked the story of Nasreddin called Mortal’s Way—a tale about four boys who are arguing over a bag of walnuts. The boys ask Nasreddin to divide the nuts for them. So Nasreddin says, Would you like me to divide these nuts as God divides things? Or in the way man divides things? The boys choose God’s way. (What could be better than that?) So Nasreddin gives most of the walnuts to one boy, a few to another, and one or two to the last two boys.

My mother was delighted. That’s exactly right, she said. God might be a lot of things, but fair is not one of them.

She immediately asked me to read the story to her evangelical friend.

***

So what is fair?

I studied a lot of religion and philosophy, but I avoided the topic of ethics.

But a few years ago, I almost served on a jury. I took the judge at his word when he informed potential jurors that this was our special day. Because we all now had a rare chance to learn about the great American judicial system. He encouraged each of us to ask as many questions as we wanted—something which he later regretted. I asked so many questions, I was dismissed.

Partly because of my courtroom experience, and maybe partly because of my childhood questions about our downtown jail, I was curious about teaching a class to prisoners. So when Philip Brady invited me to guest-teach my latest book, Why God Is a Woman, for his prison class, I was thrilled.

The class, done by video, involved two prisons, a men’s prison and a women’s prison.

But the prison class was nothing like I had expected. Accustomed to students who are shy, unprepared, and bored, I was surprised to find that the inmates had not only read my book, but they were eager to engage and challenge me.

What surprised me more was how socially conservative these particular men and women seemed, how middle-of-the-road their political views.

We discussed gender stereotypes, and both the men and the women said they couldn’t imagine breaking out of their traditional roles. A man explained how humiliating it would be for him to raise the children or become a care-taker. No one respects a man-mama, he said. A woman said that while she wished she could get paid the same as men, and she often felt taken advantage of by men, she couldn’t imagine being a feminist. Another woman said that she had no role model for a powerful woman, at least not one that she would want to follow.

What do you think a feminist is? I asked.

A ball-buster, one woman said. A man-hater, another joined in. A bra-burner. Others nodded in assent. In fact bra-burning seemed to be something they were all familiar with. An African American man said that he really didn’t blame those women for wanting to burn bras, but then added, Don’t blame the men for that. Maybe Jennifer Lee was right when she wrote in Time that feminism has a bra-burning myth problem.

I closed the class by reading an essay about my experience in court. Afterwards everyone went quiet. One man raised his hand.

Mrs. Andrews, he said. You don’t mind being different. I like it. But next time you get called for jury duty, I want you to dress up real nice. In a little suit. With your hair done up in a bun. Button your lips. And don’t say nothing ‘til you’re on that jury. You understand?

We laughed.

***

Since teaching that class, I have wondered about other poets’ experiences with teaching in prisons.

I began talking with my dear friend, Nicole Santalucia, who regularly teaches a prison class. She will be reporting on her experience tomorrow.

A Lucky Death

Do you, too, hesitate before you begin a writing project?

Sometimes I have an idea, but I have to wait a week or two before I can start. I scribble words on paper, alongside my grocery lists and random thoughts while I wonder, How will I ever begin?

It is during this time that I think of a story about God and Adam that my mother used to tell. The story went something like this:

After God made the body of man out of wet clay, He laid him in the sun to dry, but then He reconsidered his work. Not bad, He thought. But he sure could use a soul.

The soul, hearing God’s words and seeing the dumpy little man, said to herself, No way I’m going into that ugly thing. She flew off and hid.

(The soul, by the way, is always feminine. And always wise.)

So God had to trick the soul. He sent His angels into the clay man to play divine music of exactly the kind that the soul loved. The soul, hearing the heavenly notes coming from the clay man, could not resist. She slipped inside him but could not get out again. Not as long as the man lived.

The soul’s job was to make the man’s life worthy of the songs of angels.

Maybe the metaphor doesn’t make sense, but I think of the empty page, the pen, the idea, the scribbled notes as the writer’s clay. To bring the music and the soul into the words, that is the problem.One summer, when I was a girl, a family came to live in one of the houses on our Virginia farm. I don’t remember why they came, but I remember my mother warning me, They’re Christian Scientists. I was fascinated. They taught me all about their faith. They also read Tarot card readers and palms and saw ghosts. Mrs. Butler, the mother, had a caged bird that she insisted was an angel, even after it died and lay on its feathered back, talons to the sky. She had a white toy poodle who she said could count. She would say, three, and the little dog would yap, yap, yap. She said she could talk to animals, and they would talk to me, too, if I could figure out how to listen.

She had me sit in silence and listen.

I was enthralled. That summer I learned how to read palms and how to tell if I was pregnant.

One day I read the palms of one of the farmhands who quit immediately after my reading, telling my parents I was a witch.

Mrs. Butler said I’d know when I was pregnant when a child’s soul came into my room at night. The soul would check me out before descending into life. Like a fairy or a ghost, a soul leaves tracks.

Like what? I asked, and she said like spilled salt, running faucets, open windows, and dreams—peculiar dreams.

Mrs. Butler claimed that she had dreamt of a brunette girl as small as a pine cone before her daughter, Bonnie, was born. Her other children never made it into human form, she said, meaning what, I wasn’t certain.

Mrs. B. said that the same thing happens at the end of life. Only more so. The soul often hesitates before leaving the body behind. The soul worries that she hasn’t done what she was meant to do.

For many souls, this means death happens not once but several times.

This is another story I think of as metaphor.

How many times I have tried to finish a writing project, only to go back and see I have more work to do.

My memories of Mrs. Bulter remind me of this passage from Yeats’ Celtic Passage“By the Hospital Lane goes the Faeries Path. Every evening they travel from the hill to the sea, from the sea to the hill. At the sea end of their path stands a cottage. One night Mrs. Arbunathy, who lived there, left her door open, as she was expecting her son. Her husband was asleep by the fire; a tall man came in and sat down beside him. After he had been sitting for a while, the woman said, ‘In the name of God, who are you?’ He got up and went out, saying, ‘Never leave the door open at this hour, or evil will come to you.’ She woke her husband and told him. ‘One of the Good People has been with us,’[ he said.

***

My friend, S., who practices Chinese medicine, tells me I should learn not to rush into things. I am in too much of a hurry. The threshold moments, as she calls them, those moments spent before opening or closing a door, are invaluable to life.

She described to me something she calls a lucky death, or a death one enters with awareness. Usually a lucky death takes a week or two to complete.

One lingers in the foyer, waiting before closing the last door. And opening Death’s Door.

According to her, in the last days of life, a person can experience the final light show of the soul, a show that can go on for days. In that time, her life is illuminated before her.

I was reminded of my mother’s death. How two weeks before she died, we all gathered around for what we thought was the last time, only to see her miraculously regain a little strength for one last week.

Her hospice worker, like S., said this happens quite often. There is a last burst of energy before the end.

***

As a college student in a religious studies class, I remember pondering the Buddhist belief that it is essential to come to terms with death if one is to come to grips with life.

How do I do that? I asked. One student stood up and announced that he knew exactly how. Because he personally knew God and Satan and Jesus and all the heavenly hosts. In fact had had several chats with Jesus just the night before. But it turned out that he was having a psychotic episode. He had to leave college for the rest of the semester.

In my recent book, Why God Is a Woman, I imagined Death’s Door as an actual door that must be hidden. Otherwise curious children will open it on a dare to see what was on the other side.

I was inspired by those etchings by William Blake of Death’sDoor, particularly the one of a youth resting above a tomb, and an old man ducking through the half-open door, walking stick in hand. I imagined that the youth was like a young writer imagining his future. He imagines that he will write the next Great American Novel. Or be the new Whitman.

The old man, bent and lined, is the writer after he has finished his work. Or rather, after his work has finished with him. He has no more visions of grandeur.

Today I feel like that old man as I finish my latest writing project—totally spent, exhausted, and depressed. I am unsure what is behind the next door.

In my last post for Best American Poetry's blog, I compared confessional writing to snake handling and taxidermy. pointing out that taxidermy is like writing about the dead, while snake handling is like writing about the living. I left the topic of snake handling untouched, largely because I am not enthusiastic about writing about my living relatives and friends. But I recently received an email asking me to elaborate on the topic of snake handling. Really, Nin? Do you handle snakes? I was asked.

I thought I’d start by describing the day I first tried to hold a snake. My sister, D., had just returned from Nature Camp. It was a hot summer day, and I was so happy to see her when she announced, Snakes are really neato, Nin. (Neato was the word back then.) And they're a cinch to catch. Wanna try? I didn’t answer her. She went on to tell me about the herpetologist who was her camp counselor—how he had told her that we are never more than a few feet from a snake in Virginia. To prove his point, she reached out and grabbed a small Eastern Garter snake that was gliding into the Johnson grass by the car, and held it out to me. Grab him beneath the neck, she said. I didn’t point out that snakes don’t have necks. Instead I quickly dropped the snake and jumped back.

Are you scared of a little garter snake? she asked.

Not exactly, I wanted to say. But I don’t want to hold onto one. I just get this feeling . . .

That’s the feeling I have when I pick up my pen and think about trying to write about the secrets or revealing moments of someone I know, especially someone I love or once loved. I’m even feeling it a little bit now as I write about my sister.

The experience makes me think of those early writing classes when everyone was trying to follow the dictum, Write what you know. Our writing material, we were informed, is all around us. You don’t need or want to imitate Poe or Whitman to be a poet. Many of us were reading Ann Sexton and Sylvia Plath and using them as role models. The more distressing the material, the more applauded our poetry seemed to be. I felt as if I were trying to grab the creepy or unsavory moments from my days and hold them up for everyone to see. I remember wondering if Wordsworth had been a confessional poet, would he have defined poetry as creepiness recollected in tranquility? Or the spontaneous overflow of toxic feelings?

I will always remember one of my early poetry workshops in which a woman’s poems described her boyfriend’s sexual inadequacies, giving a detailed account of his penis and freckled ass. The poems were graphic to the point of pornographic, and they were hard to erase from my mind. I can’t tell you whether the poems were any good or not, but I can say that the boyfriend was in my philosophy class. I was never able to look at him without wondering if the poems were accurate.

But I don’t mean to suggest that all of our poems in those days were so deeply personal or potentially humiliating. No, many were as innocuous and commonplace as garden-variety black snakes, milk snakes, or the red bellied snakes. The appeal of the poems, I realized after a while, relied not on what they confessed, but rather on how much they could startle and entertain a reader. After a while, I became accustomed to the style of poetry, even if I never mastered it.

In this same way, I became accustomed as a girl to the many harmless snakes that cohabitated with us in our childhood home. I don’t know at what point it became commonplace to open a closet or look under the sink and discover a snake curled up in the corner behind a shoe or a bottle of dish soap. Those of you who have lived in the rural South might know how much snakes do like to come inside in the fall, along the field mice. As a girl, I would sometimes wake in the night and hear a distinct swishing sound of a blacksnake gliding across the attic floor overhead. When I complained to my parent, my mother insisted that the snakes were our friends. We should be happy they were living in our attic. They dined on the rodents that had also moved into the attic and, unlike the Orkin man, they left no chemical residue behind.

When I went into the attic in spring to find my summery clothes, I would often discover a few snake skins that were several feet long.

I suppose I am stating the obvious here to say that the older I grew, the more aware I became of just how peculiar my family was. How many odd little tales I could tell, as I am telling now. But often I chose not to.

There is something complicated about writing about your close friends and family, even if it is so done these days, and often done so well. I doubt I’m unique in my hesitations. I recently finished a collection of novels, the Neopolitan Novels, written by an Italian author whose pen name is Elena Ferrante. What fascinated me about the books was the vivid and exhaustive descriptions of a lifelong rivalry and love/hate relationship between two women, one of whom is a writer. The promise that is broken and that ultimately breaks up their friendship is the promise of the writer—not to write about her friend. I couldn’t help but think that Ferrante’s hidden identity allowed her a level of honesty and the freedom to describe I am in awe at her ability to delve so deeply into the female psyche.

By contrast I feel a lack of courage, though once or twice, I have written about my father who was, among other things, a gay man who was kicked out of the Navy for having an affair with an officer, and who underwent counseling to be “cured.” I don’t know what his counseling entailed, and I have often wondered. My mother married him, knowing he was gay, and never expected him to be otherwise. I know of several books about the suffering caused by the gay/straight marriage, but the books don’t describe my parents. My mother, a pragmatist, was very open about her belief that homosexuality is genetic, and she quite eagerly looked at each of her six children to see which of us had inherited the gay gene. Once, after asking one of my sisters if she was a lesbian, my mother speculated that the gene might skip generations, sort of like red hair. My father, however, was not forthcoming about his sexuality, though he kept photos and letters from an ex-lover in his sock drawer and always had gay friends. To write about his sexuality used to feel like a violation, but nowadays, the topic is so much tamer than it once was, I don’t feel as if I am trespassing when I write about him.

Maybe part of the problem I have hadwith confessional poetry is that it so often involves confessing another’s secrets, not my own. I have one poet-friend who wrote a lot of very revealing poems about her family and then informed her siblings and parents that her poems had nothing to do with them. Any unflattering resemblance to reality was not intentional. But she was lying, and no one was fooled. As a result, she is still not particularly welcome or comfortable at family functions. She says her family keeps asking her why she cast them in such an unflattering light. How can I tell them—they’re just poems, she asked me, meaning, What did they expect? Hallmark cards? She added, Why can’t they just chill?

Her use of the word, chill, reminds me of the day my sister decided to catch a few copperheads and photograph them. She wanted the snakes to remain still or move slowly, so she put the copperheads in the deep freeze so they would cool down and slow for her photo shoot. Imagine me, reaching unsuspecting into the freezer for a Nutty Buddy and finding a few half-frozen snakes.

Generally, I think, families like those snakes do chill out. They get used to their poet-sibling, parents, or children. They learn to tolerate a certain amount of exposure with grace. Maybe they realize that the slim volumes of poetry are rarely read. Perhaps it is that anonymity that makes us poets brave. Most of us know that the chances of our getting a decent audience are minimal. I think I, for one, could have written entire volumes about my family, and they would never know, much less read them.

All the same, I still think of reasons to hesitate. I had a student in a workshop once who asked me if she could get sued for a poem she wrote about her abusive yet ultra-wealthy ex-lover. I don’t know the answer, but I suppose it might be possible. I don’t think that’s happened, or has it? This woman said that she’d always felt like a mouse in a lion den, something vulnerable and small. She also admitted she wanted revenge. Even if it were just in a poem. And she added, There is something magical about the power of words.

To keep pushing the snake analogy, I was reminded by her of the winter my sister bought a boa constrictor at the pet store. Her boa had a short and tragic life. A few weeks later, the snake’s dinner, a small white mouse, ate it, crunching into its long body while the snake lay motionless in a glass aquarium on our living room table. When I pointed out the mouse-eating snake, my mother looked up from her newspaper and sighed. To think, I thought someone was eating Triscuits in here. Nature is just full of surprises, isn’t it? My mother, an Ancient Greek scholar, then alluded to the Spartan women who beat up any men who failed to perform their studly duties. Exactly what the Spartan ladies had to do with snake-eating mice, I wasn't certain, though the image has stuck with me.

This same poet who talked of seeking revenge through poetry also claimed that writing about her suffering was healing, which surprised me—I who am so squeamish. I am reminded me of the day I told my mother I didn’t want to handle a snake, that I was afraid of them. She said how stupid I was, adding, snakes are among the most valuable citizens of the natural world. Why do you think snakes were a symbol of healing in Ancient Greece?

I asked if they were also a healing symbol of Sparta, but she didn’t answer. Some people just have a way with snakes, she continued. They know their secret language, just as bird lovers know bird songs. Her friend, Polly Buxton, she informed me, could pick up rattle snakes with her walking stick. All she had to do was plant her stick on the ground, and they'd wrap around it like ribbons around a Maypole. I didn’t point out that Polly also talked to ghosts and said she had met Abraham Lincoln more than once, adding God rest his soul.

My mother then lectured me on how I should learn to love all of nature, snakes included. She told me again and again her favorite snake tale about our distant relative, Mr. Frick, who often visited an island in the Caribbean and brought snakes back home with him on the planes (decades before the movie). In order to sneak his Caribbean snake collection through customs, he dressed his three little daughters up like Little Bo Peeps, complete with bonnets and baskets. The snakes he hid in the bottom of their baskets. The snakes, Mom claimed, slept through the entire plane ride and were never discovered by U.S. customs agents. Those little Frick girls kept them so happy. Why they must have been snake enchantresses.

She told this story many times as if she were telling one of the miracles of Jesus. Only she added, This really happened. And: Imagine being that much in love with snakes. I know she wished I were more like my sister and those little Fricks. She hoped one day I too might grow up and learn to hold onto a snake. As she put it, snake-handling is a life skill. Sort of like riding a bike, only much more useful. Once you learn it, you never forget. I’m still thinking about that, and I am still thinking about how to write a good confessional poem.

My father once said, If you ever speak in public, lower your voice. Stand tall, square your shoulders, and look confident. And wear a nice jacket, like a suit jacket. I would practice in front of the mirror, lowering my voice, wearing one of his large men’s jackets that smelled of him—of whiskey and talcum powder.

Actually I am lying. My father never said how I should speak in public. Instead he made fun of my mother when she became an activist, speaking out at town meetings, her face turning red, her voice quivering. Several times her photo was on the front of the newspaper. Her voice gets so high, my father said. And shrill. And she wears the wrong dresses. And looks old in the photographs.

In other words, she looked and sounded like a middle-aged woman. My father asked her to use her maiden name if she was ever going to be interviewed again.

I’ve thought about this a lot since then, especially when I listen to women candidates like Hillary Clinton speak. She lowers her voice. She squares her shoulders. She looks confident, if tired. God forbid if she should ever become emotional or shrill. One could guess that her feminine side is not an asset.

My father was not critical of the men who spoke out at the same town meetings as my mother, and who were also featured in the newspaper. None of them looked appealing. Most of them were balding white men in suits. Nor did my father grade the timbre of their voices. I asked if they spoke well, and he said in an absent-minded voice, Not particularly.

That’s the first time it occurred to me that you can get away with a lot if you are a man and not much if you are a woman.

I’ve tried to make this point in many ways, and most recently in my book, Why God Is a Woman, in which I envisioned an imaginary world where gender roles are reversed. But again and again, I hear men argue with me, saying, We have it just as hard.

I beg to differ. Men, I want to say, get away with what my father called a-hell-of-alot.

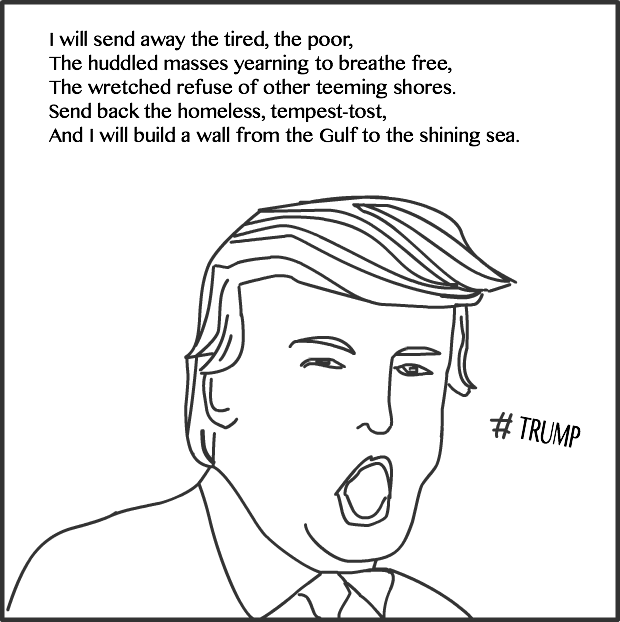

Donald Trump is my case in point.

Imagine, if you will, a balding, orange woman, running for president. How long would you last?

Now imagine a balding, orange woman with no experience, running for president.

Imagine this orange, balding and female candidate, married to her third young male sex toy.

Yes, go ahead. Let yourself imagine a rich and powerful woman, a Trumpette, that likes to think of men as her possession, to be discarded with age.

Now imagine this orange, balding woman who does nothing but brag nonstop, and who is running for president.

(Modesty, we women know, is one of our many assets. What do men know about modesty?)

Then imagine this same balding woman-candidate making fun of others, maybe enjoying telling John McCain that he’s no war hero, as if she knows exactly what a war hero is.

Really, imagine what would happen if Hillary Clinton made fun of John McCain.

Imagine this hideous orange woman-candidate, announcing what a sexy thing she is, bragging about her breast size as Donald Trump went on about his penis size.

Imagine this Trumpette saying about her son If Ivan weren’t my son, perhaps I’d be dating him. Or talking about her newborn boy and wondering about the size his sex might be in the future—as Donald Trump did when looking at his baby Tiffany’s breasts.

I grew up on a farm, and one of my earliest memories is of animals dying, and of my mother saying, It's just a dog. Or, it's just a cat. Or it's just a calf, meaning, Stop crying. Death is just a part of life. And besides, there is a whole barnyard of other pets.

My mother was tough. Or, as my father put it, She's from New England. She almost never cried and was rarely emotional.

I remember watching her unflinching face as she loaded her horse onto a trailer to be trucked off to the glue factory. Or when she found a few of her heifers, dead from the bloat after eating alfalfa. Only in her later years did she become teary over the death of her Rottweiler, and even then, it was just a solitary tear, blinked back with a stoic expression, It happens to all of us, as if it were just the fact of death that we needed to get used to, not the loss of some part of ourselves, of some kind of communion we have with our animal friends.

My father was different. He expressed his feelings of both rage and grief openly. In fact, he had trouble controlling himself at times and could be a like a can of hot, shook Coke.

I remember the two of us holding his boxer, Tonic, while the dog died. We wept while my mother looked on, appalled by our outpouring.

It was that memory of my father and I and Tonic that came to me in a dream, a healing dream I had a few years after my father passed away. I wanted so badly to remember the dream, I bought a puppy the next week and named it Sadie, which was a name that was somehow a part of that dream.

In the first year of her life, Sadie was so sickly, one vet suggested she might not survive. During that year I often dreamt of my father. We had had our issues, you could say, but little by little over that year, the issues began to dissipate. I dreamt of him less and less. And Sadie's health began to improve. By the time Sadie was a year old, the father dreams had stopped, and Sadie was a healthy dog.

Don't get me wrong, I know these parallels are merely coincidental, but the link is there in my mind. I think of Sadie as a healing force, but I think most dogs are just that.

Sadie became my writing companion, my walking companion, and my best listener as well. Over the last thirteen years, she has heard every poem I have ever written at least twenty times. You could say that she is my most patient and devoted listener. She looks up at me, alert, as if interested in every word.

After a year, I bought her a friend, Froda, and the two dogs are inseparable. They have kept me going, hour and hour, day after day.

In the fall of 2015, Sadie was diagnosed with kidney disease. At the diagnosis, we were told to expect less than a year because her numbers were very bad. But she has been going strong in spite of those numbers with a few setbacks . . .

until this week. I can hear my mother telling me, She's just a dog. And of course she is. Just like I am just a woman.

It is unspeakably sad for me.

Farm-girl that I was, I have never taken as animal to be put down. The farm dogs simply died, as did the cats. Some went off to corners. Some were held as Tonic was. But I never chose the day they would leave.

I am such a fan of Rumi. I LOVE the last lines of this Rumi poem.

These spiritual window-shoppers,

who idly ask, 'How much is that?' Oh, I'm just looking.

They handle a hundred items and put them down,

shadows with no capital.

What is spent is love and two eyes wet with weeping.

But these walk into a shop,

and their whole lives pass suddenly in that moment,

in that shop.

Where did you go? "Nowhere."

What did you have to eat? "Nothing much."

Even if you don't know what you want,

buy _something,_ to be part of the exchanging flow.

Start a huge, foolish project,

like Noah.

It makes absolutely no difference

what people think of you.

From Rumi, 'We Are Three', Mathnawi VI, 831-845

I am so dependent on books, I sometimes feel bereft when I finish one. It’s a little like losing a lover, esp. if it’s a really good book/lover.

I like to have three books on hand—a poetry book, a novel, and a spiritual book that keeps me sane.

This week my poetry book is Matthew Minicucci’s Translation, which I just discovered at a Lit Youngstown Reading, and I am savoring . . . Oh, I love finding a new poet to spend time with.

But I always want to be in the middle of a novel.

These last few weeks I have been swept up by the Elena Ferrante Neapolitan Novels—a set of 4 books that so vividly describe the love/hate or maybe love/jealousy relationship between two women, they sounded almost autobiographical.

Sometimes the author goes on for pages and pages, describing the insecurities and jealousies of the main character, and often there isn’t a driving plot.

So why is she so interesting? And I mean hundreds of repetitive pages worth of interesting? I don't know. I really don't.

Like so many of her readers, I want to know who the real Ferrante is. Elena Ferrante is a nom de plume.

I suppose part of the appeal (but only a small part) is that the book brought up my own memories, some of my own brilliant friend, Anne Marie Slaughter, although I didn’t feel jealous of her as a girl. Rather, I somehow took personal pride in her brilliance, as if it had something to do with me. I still feel that way. (Funny, the logic of childhood.)

The main character also talks a lot about her teachers, those from childhood and beyond.And she talks about luck. She feels grateful. I do the same, babbling on and on . . .

I am so very grateful for the great professors who helped me.

Though sometimes the “greatness” of my profs was served up via negative. The first writing teacher I had was Diane Wakoski. As a freshman, I had finagled my way into her graduate writing class. At the time, I was writing truly awful poems.Wakoski, or Whak Me, as I called her, told me on no uncertain terms just how terrible my poetry was--week after week, day after day. I consoled myself with the fact that I wasn't her only victim. I can’t say I have fond memories of her class, but she was honest and saved me some time by telling the truth. Since then I have often wondered-- What is the appropriate response to terrible poetry? How does one say, graciously, what Diane said without any pretense of kindness?

The next professor I often feel thankful for is Michael Burkhard. Michael taught me, among other things, the fish bowl cure for bad poems. The fishbowl, he said, can save many a disastrous poem. And I only had bad poems then. So what is the fish bowl cure? you might ask.

Write a letter or two and then a poem or two. Then you take your poems and letters, cut them up, sentence by sentence, and put then in a bowl. Stir them around and then take them out and arrange the lines on your page.

I learned from Michael that poetry can be fun. It can be a kind of play. A puzzle. A discovery. Now, sometimes I will be reading a poem that has surprising connections, and I wonder if the writer used the fishbowl cure.

And then there is David Lehman for whom I feel such profound gratitude. A class with Lehman was like drinking ten cups of espresso at once. It was a shot of adrenaline, joy, love.

After every class, I wanted to read or write another poem asap. Through David, I discovered Borges, Michaux, Vallejo, Marquez, Ashbery, O’Hara, Strand, and so many others. And for a while (just a little while), I lost that critical voice that said, You’re no poet. And, Who do you think you are?

Unlike Wakoski, I don’t remember David ever saying that he disliked someone’s poem. When confronted with a poem he disliked, he would stare blankly at the page, all emotion vacuumed from his features. I suppose he didn’t need to say anything. But he celebrated what he loved, even if it was just a line or a single word. Every now and then, I felt celebrated. And lucky. He was an antidote to the Whak Me experience.

What is it about going to the beauty parlor that fries the brain? And you go back and try to write and all you can think is, Was that me in the mirror? Oh dear. And then there are those questions . . . You write? What do you write? Do you get paid? Why do you do it then?

I am so exhausted after writing sometimes, I can barely see straight. I am just finishing my next book, and that is always the hardest time for me.